A man, of small stature, found himself standing alone on a prairie. He thought to himself, “How came I here? Are there no beings on this earth but myself? I must travel and see. I must walk till I find the abodes of men.”

So soon as his mind was made up, he set out, he knew not whither, in search of habitations. He was a resolute little fellow, and no difficulties could turn him from his purpose: neither prairies, rivers, woods nor storms, had the effect to daunt his courage or turn him back. After traveling a long time, he came to a wood, in which he saw decayed stumps of trees, as if they had been cut in ancient times, but no other trace of men. Pursuing his journey, he found more recent marks of the same kind; after this, he came upon fresh traces of human beings; first their footsteps, and then the wood they had felled, lying in heaps. Pushing on, he emerged toward dusk from the forest, and beheld at a distance a large village of high lodges standing on rising ground.

“I am tired of this dog-trot,” he said to himself. “I will arrive there on a run.”

He started off with all his speed. On coming to the first lodge, without any especial exertion, he jumped over it, and found himself standing by the door on the other side. Those within saw something pass over the opening in the roof; they thought from the shadow it cast that it must have been some huge bird—and then they heard a thump upon the ground. “What is that?” they all said and several ran out to see.

They invited him in, and he found himself in company with an old chief and several men who were seated in the lodge. Meat was set before him; after which the old chief asked him whither he was going, and what was his name. He answered that he was in search of adventures, and that his name was “Grasshopper.”

They all opened their eyes upon the stranger with a broad stare.

“Grasshopper!” whispered one to another; and a general titter went round.

They invited him to stay with them, which he was inclined to do; for it was a pleasant village, but so small as to constantly embarrass Grasshopper. He was in perpetual trouble; whenever he shook hands with a stranger, to whom he might be introduced, such was the abundance of his strength, without meaning it, he wrung his arm off at the shoulder. Once or twice, in mere sport, he cuffed the boys, about the lodge, by the side of the head, and they flew out of sight as though they had been shot from a bow; nor could they ever be found again, though they were searched for in all the country round, far and wide. If Grasshopper proposed to himself a short stroll in the morning, he was at once miles out of town. When he entered a lodge, if he happened for a moment to forget himself, he walked straight through the leathern, or wooden, or earthen walls, as if he had been merely passing through a bush. At his meals he broke in pieces all the dishes, set them down as lightly as he would; and putting a leg out of bed when he rose, it was a common thing for him to push off the top of the lodge.

He wanted more elbow-room; and after a short stay, in which, by the accidentally letting go of his strength, he had nearly laid waste the whole place, and filled it with demolished lodges and broken pottery, and one-armed men, he made up his mind to go further, taking with him a young man who had formed a strong attachment for him, and who might serve him as his pipe-bearer; for Grasshopper was a huge smoker, and vast clouds followed him wherever he went; so that people could say, “Grasshopper is coming!” by the mighty smoke he raised.

They set out together, and when his companion was fatigued with walking, Grasshopper would put him forward on his journey a mile or two by giving him a cast in the air, and lighting him in a soft place among the trees, or in a cool spot in a water-pond, among the sedges and water-lilies. At other times he would lighten the way by showing off a few tricks, such as leaping over trees, and turning round on one leg till he made the dust fly; at which the pipe-bearer was mightily pleased, although it sometimes happened that the character of these gambols frightened him. For Grasshopper would, without the least hint of such an intention, jump into the air far ahead, and it would cost the little pipe-bearer half a day’s hard travel to come up with him; and then the dust Grasshopper raised was often so thick and heavy as to completely bury the poor little pipe-bearer, and compel Grasshopper to dig diligently and with might and main to get him out alive.

One day they came to a very large village, where they were well received. After staying in it some time (in the course of which Grasshopper, in a fit of abstraction, walked straight through the sides of three lodges without stopping to look for the door), they were informed of a number of wicked spirits, who lived at a distance, and who made it a practice to kill all who came to their lodge. Attempts had been made to destroy them, but they had always proved more than a match for such as had come out against them.

Grasshopper determined to pay them a visit, although he was strongly advised not to do so. The chief of the village warned him of the great danger he would incur, but finding Grasshopper resolved, he said:

“Well, if you will go, being my guest, I will send twenty warriors to serve you.”

Grasshopper thanked him for the offer, although he suggested that he thought he could get along without them, at which the little pipe-bearer grinned, for his master had never shown in that village what he could do, and the chief thought that Grasshopper, being little himself, would be likely to need twenty warriors, at the least, to encounter the wicked spirits with any chance of success. Twenty young men made their appearance. They set forward, and after about a day’s journey they descried the lodge of the Manitoes.

Grasshopper placed his friend, the pipe-bearer, and the warriors, near enough to see all that passed, while he went alone to the lodge.

As he entered, Grasshopper saw five horrid-looking Manitoes in the act of eating. It was the father and his four sons. They were really hideous to look upon. Their eyes were swimming low in their heads, and they glared about as if they were half starved. They offered Grasshopper something to eat, which he politely refused, for he had a strong suspicion that it was the thigh-bone of a man.

“What have you come for?” said the old one.

“Nothing,” answered Grasshopper; “where is your uncle?”

They all stared at him, and answered:

“We ate him, yesterday. What do you want?”

“Nothing,” said Grasshopper; “where is your grandfather?”

They all answered, with another broad stare:

“We ate him a week ago. Do you not wish to wrestle?”

“Yes,” replied Grasshopper, “I don’t mind if I do take a turn; but you must be easy with me, for you see I am very little.”

Pipe-bearer, who stood near enough to overhear the conversation, grinned from ear to ear when he caught this remark. The Manitoes answered:

“Oh yes, we will be easy with you.”

And as they said this they looked at each other, and rolled their eyes about in a dreadful manner. A hideous smile came over their faces as they whispered among themselves:

“It’s a pity he’s so thin. You go,” they said to the eldest brother.

The two got ready—the Manito and Grasshopper—and they were soon clinched in each other’s arms for a deadly throw. Grasshopper knew their object—his death; they wanted a taste of his delicate little body, and he was determined they should have it, perhaps in a different sense from that they intended.

“Haw! haw!” they cried, and soon the dust and dry leaves flew about as if driven by a strong wind. The Manito was strong, but Grasshopper thought he could master him; and all at once giving him a sly trip, as the wicked spirit was trying to finish his breakfast with a piece out of his shoulder, he sent the Manito head-foremost against a stone; and, calling aloud to the three others, he bade them come and take the body away.

The brothers now stepped forth in quick succession, but Grasshopper having got his blood up, and limbered himself by exercise, soon dispatched the three—sending one this way, another that, and the third straight up into the air, so high that he never came down again.

It was time for the old Manito to be frightened, and dreadfully frightened he got, and ran for his life, which was the very worst thing he could have done; for Grasshopper, of all his gifts of strength, was most noted for his speed of foot. The old Manito set off, and for mere sport’s sake, Grasshopper pursued him. Sometimes he was before the wicked old spirit, sometimes he was flying over his head, and then he would keep along at a steady trot just at his heels, till he had blown all the breath out of the old knave’s body.

Meantime his friend, the pipe-bearer, and the twenty young warriors, cried out:

“Ha, ha, ah! ha, ha, ah! Grasshopper is driving him before him!”

The Manito only turned his head now and then to look back. At length, when he was tired of the sport, to be rid of him, Grasshopper, with a gentle application of his foot, sent the wicked old Manito whirling away through the air, in which he made a great number of the most curious turn-overs in the world, till he came to alight, when it so happened that he fell astride of an old bull-buffalo, grazing in a distant pasture, who straightway set off with him at a long gallop, and the old Manito has not been heard of to this day.

The warriors and the pipe-bearer and Grasshopper set to work and burned down the lodge of the wicked spirits, and then when they came to look about, they saw that the ground was strewn on all sides with human bones bleaching in the sun; these were the unhappy victims of the Manitoes. Grasshopper then took three arrows from his girdle, and after having performed a ceremony to the Great Spirit, he shot one into the air, crying, “You are lying down; rise up, or you will be hit!”

The bones all moved to one place. He shot the second arrow, repeating the same words, when each bone drew toward its fellow-bone; the third arrow brought forth to life the whole multitude of people who had been killed by the Manitoes. Grasshopper conducted the crowd to the chief of the village, who had proved his friend, and gave them into his hands. The chief was there with his counselors, to whom he spoke apart.

“Who is more worthy,” said the chief to Grasshopper, “to rule than you. You alone can defend them.”

Grasshopper thanked him, and told him that he was in search of more adventures. “I have done some things,” said little Grasshopper, rather boastfully, “and I think I can do some more.”

The chief still urged him, but he was eager to go, and naming pipe-bearer to tarry and take his place, he set out again on his travels, promising that he would some time or other come back and see them.

“Ho! ho! ho!” they all cried. “Come back again and see us!” He renewed his promise that he would; and then set out alone.

After traveling some time he came to a great lake, and on looking about he discovered a very large otter on an island. He thought to himself, “His skin will make me a fine pouch.” And he immediately drew up at long shots, and drove an arrow into his side. He waded into the lake, and with some difficulty dragged him ashore, and up a hill overlooking the lake.

As soon as Grasshopper got the otter into the sunshine where it was warm, he skinned him, and threw the carcass some distance off, thinking the war-eagle would come, and that he should have a chance to secure his feathers as ornaments for the head; for Grasshopper began to be proud, and was disposed to display himself.

He soon heard a rushing noise as of a loud wind, but could see nothing. Presently a large eagle dropped, as if from the air, upon the otter’s carcass. Grasshopper drew his bow, and the arrow passed through under both of his wings. The bird made a convulsive flight upward, with such force that the cumbrous body was borne up several feet from the ground; but with its claws deeply fixed, the heavy otter brought the eagle back to the earth. Grasshopper possessed himself of a handful of the prime feathers, crowned his head with the trophy, and set off in high spirits on the look out for something new.

After walking awhile, he came to a body of water which flooded the trees on its banks—it was a lake made by beavers. Taking his station on the raised dam where the stream escaped, he watched to see whether any of the beavers would show themselves. A head presently peeped out of the water to see who it was that disturbed them.

“My friend,” said Grasshopper, in his most persuasive manner, “could you not oblige me by turning me into a beaver like yourself. Nothing would please me so much as to make your acquaintance, I can assure you;” for Grasshopper was curious to know how these watery creatures lived, and what kind of notions they had.

“I do not know,” replied the beaver, who was rather short-nosed and surly. “I will go and ask the others. Meanwhile stay where you are, if you please.”

“To be sure,” answered Grasshopper, stealing down the bank several paces as soon as the beaver’s back was turned.

Presently there was a great splashing of the water, and all the beavers showed their heads, and looked warily to where he stood, to see if he was armed; but he had knowingly left his bow and arrows in a hollow tree at a short distance.

After a long conversation, which they conducted in a whisper so that Grasshopper could not catch a word, strain his ears as he would, they all advanced in a body toward the spot where he stood; the chief approaching the nearest, and lifting his head highest out of the water.

“Can you not,” said Grasshopper, noticing that they waited for him to speak first, “turn me into a beaver? I wish to live among you.”

“Yes,” answered their chief; “lie down.” And Grasshopper in a moment found himself a beaver, and was gliding into the water, when a thought seemed to strike him, and he paused at the edge of the lake. “I am very small,” he said, to the beaver, in a sorrowful tone. “You must make me large,” he said; for Grasshopper was terribly ambitious, and wanted always to be the first person in every company. “Larger than any of you; in my present size it’s hardly worth my while to go into the water.”

“Yes, yes!” said they. “By and by, when we get into the lodge it shall be done.”

They all dived into the lake, and in passing great heaps of limbs and logs at the bottom, he asked the use of them; they answered, “It is for our winter’s provisions.”

When they all got into the lodge their number was about one hundred. The lodge was large and warm.

“Now we will make you large,” said they. “Will that do?”

“Yes,” he answered; for he found that he was ten times the size of the largest.

“You need not go out,” said the others; “we will bring you food into the lodge, and you will be our chief.”

“Very well,” Grasshopper answered. He thought, “I will stay here and grow fat at their expense.” But, soon after, one ran into the lodge, out of breath, crying out, “We are visited by the Indians!”

All huddled together in great fear. The water began to lower, for the hunters had broken down the dam, and they soon heard them on the roof of the lodge, breaking it up. Out jumped all the beavers into the water, and so escaped.

Grasshopper tried to follow them; but, unfortunately, to gratify his ambition, they had made him so large that he could not creep out at the hole. He tried to call them back, but either they did not hear or would not attend to him; he worried himself so much in searching for a door to let him out, that he looked like a great bladder, swollen and blistering in the sun, and the sweat stood out upon his forehead in knobs and huge bubbles.

Although he heard and understood every word that the hunters spoke—and some of their expressions suggested terrible ideas—he could not turn himself back into a man. He had chosen to be a beaver, and a beaver he must be. One of the hunters, a prying little man, with a single lock dangling over one eye—this inquisitive little fellow put his head in at the top of the lodge. “Ty-au!” cried he. “Tut ty-au! Me-shau-mik—king of beavers is in.” Whereupon the whole crowd of hunters began upon him with their clubs, and knocked his scull about until it was no harder than a morass in the middle of summer. Grasshopper thought as well as ever he did, although he was a beaver; and he felt that he was in a rather foolish scrape, inhabiting the carcass of a beaver.

Presently seven or eight of the hunters hoisted his body upon long poles, and marched away home with him. As they went, he reflected in this manner: “What will become of me? My ghost or shadow will not die after they get me to their lodges.”

Invitations were immediately sent out for a grand feast; but as soon as his body got cold, his soul being uncomfortable in a house without heat, flew off.

Having reassumed his mortal shape, Grasshopper found himself standing near a prairie. After walking a distance, he saw a herd of elk feeding. He admired their apparent ease and enjoyment of life, and thought there could be nothing more pleasant than the liberty of running about and feeding on the prairies. He had been a water animal and now he wished to become a land animal, to learn what passed in an elk’s head as he roved about. He asked them if they could not turn him into one of themselves.

“Yes,” they answered, after a pause. “Get down on your hands and feet.”

He obeyed their directions, and forthwith found himself to be an elk.

“I want big horns, big feet,” said he; “I wish to be very large;” for all the conceit and vain-glory had not been knocked out of Grasshopper, even by the sturdy thwacks of the hunters’ clubs.

“Yes, yes,” they answered. “There,” exerting their power, “are you big enough?”

“That will do,” he replied; for, looking into a lake hard by, Grasshopper saw that he was very large. They spent their time in grazing and running to and fro; but what astonished Grasshopper, although he often lifted up his head and directed his eyes that way, he could never see the stars, which he had so admired as a human being.

Being rather cold, one day, Grasshopper went into a thick wood for shelter, whither he was followed by most of the herd. They had not been long there when some elks from behind passed the others like a strong wind, calling out:

“The hunters are after us!”

All took the alarm, and off they ran, Grasshopper with the rest.

“Keep out on the plains,” they said. But it was too late to profit by this advice, for they had already got entangled in the thick woods. Grasshopper soon scented the hunters, who were closely following his trail for they had left all the others and were making after him in full cry. He jumped furiously, dashed through the underwood, and broke down whole groves of saplings in his flight. But this only made it the harder for him to get on, such a huge and lusty elk was he by his own request.

Presently, as he dashed past an open space, he felt an arrow in his side. They could not well miss it, he presented so wide a mark to the shot. He bounded over trees under the smart, but the shafts clattered thicker and thicker at his ribs, and at last one entered his heart. He fell to the ground, and heard the whoop of triumph sounded by the hunters. On coming up, they looked on the carcass with astonishment, and with their hands up to their mouths, exclaimed: “Ty-au! ty-au!”

There were about sixty in the party, who had come out on a special hunt, as one of their number had, the day before, observed his large tracks on the plains. When they had skinned him his flesh grew cold, and his spirit took its flight from the dead body, and Grasshopper found himself in human shape, with a bow and arrows.

But his passion for adventure was not yet cooled; for on coming to a large lake with a sandy beach, he saw a large flock of brant, and speaking to them in the brant language, he requested them to make a brant of him.

“Yes,” they replied, at once; for the brant is a bird of a very obliging disposition.

“But I want to be very large,” he said. There was no end to the ambition of little Grasshopper.

“Very well,” they answered; and he soon found himself a large brant, all the others standing gazing in astonishment at his great size.

“You must fly as leader,” they said.

“No,” answered Grasshopper; “I will fly behind.”

“Very well,” rejoined the brant; “one thing more we have to say to you, brother Grasshopper” (for he had told them his name). “You must be careful, in flying, not to look down, for something may happen to you.”

“Well, it is so,” said he; and soon the flock rose up into the air, for they were bound north. They flew very fast—he behind. One day, while going with a strong wind, and as swift as their wings could flap, as they passed over a large village the Indians raised a great shout on seeing them, particularly on Grasshopper’s account, for his wings were broader than two large mats. The village people made such a frightful noise that he forgot what had been told him about looking down. They were now scudding along as swift as arrows; and as soon as he brought his neck in and stretched it down to look at the shouters, his huge tail was caught by the wind, and over and over he was blown. He tried to right himself, but without success, for he had no sooner got out of one heavy air-current than he fell into another, which treated him even more rudely than that he had escaped from. Down, down he went, making more turns than he wished for, from a height of several miles.

The first moment he had to look about him, Grasshopper, in the shape of a big brant, was aware that he was jammed into a large hollow tree. To get backward or forward was out of the question, and there, in spite of himself, was Grasshopper forced to tarry till his brant life was ended by starvation, when, his spirit being at liberty, he was once more a human being.

As he journeyed on in search of further adventures, Grasshopper came to a lodge in which were two old men, with heads white from extreme age. They were very fine old men to look at. There was such sweetness and innocence in their features that Grasshopper would have enjoyed himself very much at their lodge, if he had had no other entertainment than such as the gazing upon the serene and happy faces of the two innocent old men with heads white from extreme age afforded.

They treated him well, and he made known to them that he was going back to his village, his friends and people, whereupon the two white-headed old men very heartily wished him a good journey and abundance of comfort in seeing his friends once more. They even arose, old and infirm as they were, and tottering with exceeding difficulty to the door, were at great pains to point out to him the exact course he should take; and they called his attention to the circumstance that it was much shorter and more direct than he would have taken himself. Ah! what merry deceivers were these two old men with very white heads.

Grasshopper, with blessings showered on him until he was fairly out of sight, set forth with good heart. He thought he heard loud laughter resounding after him in the direction of the lodge of the two old men; but it could not have been the two old men, for they were, certainly, too old to laugh.

He walked briskly all day, and at night he had the satisfaction of reaching a lodge in all respects like that which he had left in the morning. There were two fine old men, and his treatment was in every particular the same, even down to the parting blessing and the laughter that followed him as he went his way.

After walking the third day, and coming to a lodge the same as before, he was satisfied from the bearings of the course he had taken that he had been journeying in a circle, and by a notch which he had cut in the door-post that these were the same two old men, all along; and that, despite their innocent faces and their very white heads, they had been playing him a sorry trick.

“Who are you,” said Grasshopper, “to treat me so? Come forth, I say.”

They were compelled to obey his summons, lest, in his anger, he should take their lives; and they appeared on the outside of the lodge.

“We must have a little trial of speed, now,” said Grasshopper.

“A race?” they asked. “We are very old; we can not run.”

“We will see,” said Grasshopper; whereupon he set them out upon the road, and then he gave them a gentle push, which put them in motion. Then he pushed them again—harder—harder—until they got under fine headway, when he gave each of them an astounding shock with his foot, and off they flew at a great rate, round and round the course; and such was the magic virtue of the foot of Grasshopper, that no object once set agoing by it could by any possibility stop; so that, for aught we know to the contrary, the two innocent, white-headed, merry old men, are trotting with all their might and main around the circle in which they beguiled Grasshopper, to this day.

Continuing his journey, Grasshopper, although his head was warm and buzzing with all sorts of schemes, did not know exactly what to do until he came to a big lake. He mounted a high hill to try and see to the other side, but he could not. He then made a canoe, and sailed forth. The water was very clear—a transparent blue—and he saw that it abounded with fish of a rare and delicate complexion. This circumstance inspired him with a wish to return to his village, and to bring his people to live near this beautiful lake.

Toward evening, coming to a woody island, he encamped and ate the fish he had speared, and they proved to be as comforting to the stomach as they were pleasing to the eye. The next day Grasshopper returned to the main land, and as he wandered along the shore he espied at a distance the celebrated giant, Manabozho, who is a bitter enemy of Grasshopper, and loses no opportunity to stop him on his journeyings and to thwart his plans.

At first it occurred to Grasshopper to have a trial of wits with the giant, but, on second thoughts, he said to himself, “I am in a hurry now; I will see him another time.”

With no further mischief than raising a great whirlwind of dust, which caused Manabozho to rub his eyes severely, Grasshopper quietly slipped out of the way; and he made good speed withal, for in much less time than you could count half the stars in the sky of a winter night, he had reached home.

His return was welcomed with a great hubbub of feasting and songs; and he had scarcely set foot in the village before he had invitations to take pot-luck at different lodges, which would have lasted him the rest of his natural life. Pipe-bearer, who had some time before given up the cares of a ruler, and fallen back upon his native place, fairly danced with joy at the sight of Grasshopper, who, not to be outdone, dandled him affectionately in his arms, by casting him up and down in the air half a mile or so, till little Pipe-bearer had no breath left in his body to say that he was happy to see Grasshopper home again.

Grasshopper gave the village folks a lively account of his adventures, and when he came to the blue lake and the abundant fish, he dwelt upon their charms with such effect that they agreed, with one voice, that it must be a glorious place to live in, and if he would show them the way they would shift camp and settle there at once.

He not only showed them the way, but bringing his wonderful strength and speed of foot to bear, in less than half a day he had transported the whole village, with its children, women, tents, and implements of war, to the new water-side.

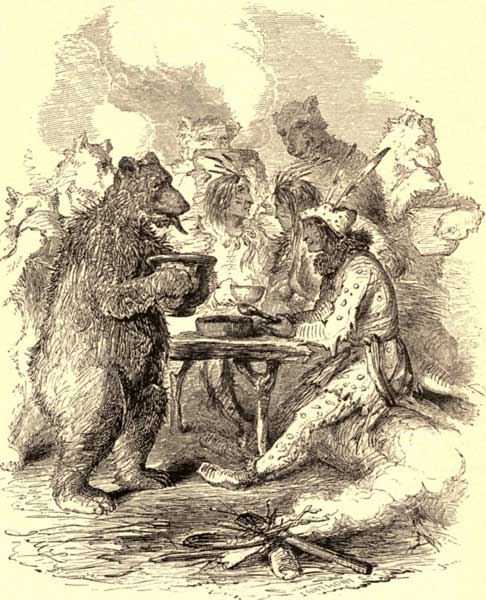

Here, for a time, Grasshopper appeared to be content, until one day a message came for him in the shape of a bear, who said that their king wished to see him immediately at his village. Grasshopper was ready in an instant; and mounting upon the messenger’s back, off he ran. Toward evening they climbed a high mountain, and came to a cave where the bear-king lived. He was a very large person; and puffing with fat and a sense of his own importance, he made Grasshopper welcome by inviting him in to his lodge.

As soon as it was proper, he spoke, and said that he had sent for him on hearing that he was the chief who was moving a large party toward his hunting-grounds.

“You must know,” said the bear-king with a terrible growl, “that you have no right there, and I wish you would leave the country with your party, or else the strongest force will take possession. Take notice.”

“Very well,” replied Grasshopper, going toward the door, for he suspected that the king of the bears was preparing to give him a hug. “So be it.”

He wished to gain time, and to consult his people; for he had seen as he came along that the bears were gathering in great force on the side of the mountain. He also made known to the bear-king that he would go back that night that his people might be put in immediate possession of his royal behest.

The bear-king replied that Grasshopper might do as he pleased, but that one of his young men was at his command; and, jumping nimbly on his back, Grasshopper rode home.

He assembled the people, and ordered the bear’s head off, to be hung outside of the village, that the bear-spies, who were lurking in the neighborhood, might see it and carry the news to their chief.

The next morning, by break of day, Grasshopper had all of his young warriors under arms and ready for a fight. About the middle of the afternoon the bear war-party came in sight, led on by the pursy king, and making a tremendous noise. They advanced on their hind-legs, and made a very imposing display of their teeth and eyeballs.

The bear-chief himself came forward, and with a majestic wave of his right hand, said that he did not wish to shed the blood of the young warriors; but that if Grasshopper, who appeared to be the head of the war-party, consented, they two would have a race, and the winner should kill the losing chief, and all his young men should be servants to the other.

Grasshopper agreed, of course—how little Pipe-bearer, who stood by, grinned as they came to terms!—and they started to run before the whole company of warriors who stood in a circle looking on.

At first there was a prospect that Grasshopper would be badly beaten; for although he kept crowding the great fat bear-king till the sweat trickled from his shaggy ears, he never seemed to be able to push past him. By and by, Grasshopper, going through a number of the most extraordinary maneuvers in the world, raised about the great fat bear-king such eddies and whirlwinds with the sand, and so danced about, before and after him, that he at last got fairly bewildered, and cried out for them to come and take him off. Out of sight before him in reaching the goal, Grasshopper only waited for the bear-king to come up, when he drove an arrow straight through him, and ordered them to take the body away and make it ready for supper; as he was getting hungry.

He then directed all of the other bears to fall to and help prepare the feast; for in fulfillment of the agreement they had become servants. With many wry faces the bears, although bound to act becomingly in their new character, according to the forfeit, served up the body of their late royal master; and in doing this they fell, either by accident or design, into many curious mistakes.

When the feast came to be served up, and they were summoned to be in attendance, one of them, a sprightly young fellow of an inquisitive turn of mind, was found upon the roof of the lodge, with his head half way down the smoke-hole, with a view to learn what they were to have for dinner. Another, a middle-aged bear with very long arms, who was put in charge of the children in the character of nurse, squeezed three or four of the most promising young papooses to death, while the mothers were outside to look after the preparations; and another, when he should have been waiting at the back of his master, had climbed a shady tree and was indulging in his afternoon nap. And when, at last, the dinner was ready to be served, they came tumbling in with the dishes, heels over head, one after the other, so that one half of the feast was spread upon the ground, and the other half deposited out of doors, on the other side of the lodge.

After a while, however, by strict discipline, and threatening to cut off their provisions, the bear-servants were brought into tolerable control.

Yet Grasshopper, with his ever restless disposition, was uneasy; and, having done so many wonderful things, he resolved upon a strict and thorough reform in all the affairs of the village. To prevent future difficulty, he determined to adopt new regulations between the bears and their masters.

With this view, he issued an edict that henceforward the bears should eat at the first table, and that the Indians were to wait upon them; that in all public processions of an honorable character the bears should go first; and that when any fighting was to be done, the Indians should have the privilege reserved of receiving the first shots. A special exemption was made in behalf of Grasshopper’s favorite and confidential adviser, the Pipe-bearer (who had been very busy in private, recommending the new order of things), who was to be allowed to sit at the head of the feast, and to stay at home with the old women in the event of battle.

Having seen his orders strictly enforced, and the rights of the bears over the Indians fairly established, Grasshopper fixed his mind upon further adventures. He determined to go abroad for a time, and having an old score to settle with Manabozho, he set out with a hope of soon falling in with that famous giant. Grasshopper was a blood relation of Dais Imid, or He of the Little Shell, and had heard of what had passed between that giant and his kinsman.

After wandering a long time he came to the lodge of Manabozho, who was absent. He thought he must play him a trick; and so he turned every thing in the lodge upside down, and killed his birds, of which there was an extraordinary attendance, for Manabozho is master of the fowls of the air, and this was the appointed morning for them to call and pay their court to him. Among the number was a raven, accounted the meanest of birds, which Grasshopper killed and hung up by the neck, to insult him.

He then went on till he came to a very high point of rocks running out into the lake, from the top of which he could see the country, back as far as the eye could reach. While sitting there, Manabozho’s mountain chickens flew around and past him in great numbers. Out of mere spite to their master, Grasshopper shot them by the score, for his arrows were very sure and the birds very plenty, and he amused himself by throwing the birds down the rocks. At length a wary bird cried out:

“Grasshopper is killing us; go and tell our father.”

Away sped a delegation of the birds which were the quickest of wing, and Manabozho soon made his appearance on the plain below. Grasshopper, who, when he is in the wrong, is no match for Manabozho, made his escape on the other side. Manabozho, who had in two or three strides reached the top of the mountain, cried out:

“You are a rogue. The earth is not so large but I can get up to you.”

Off ran Grasshopper and Manabozho after him. The race was sharp; and such leaps and strides as they made! Over hills and prairies, with all his speed, went Grasshopper, and Manabozho hard upon him. Grasshopper had some mischievous notions still left in his head which he thought might befriend him. He knew that Manabozho was under a spell to restore whatever he, Grasshopper, destroyed. Forthwith he stopped and climbed a large pine-tree, stripped off its beautiful green foliage, threw it to the winds, and then went on.

When Manabozho reached the spot, the tree addressed him: “Great chief,” said the tree, “will you give my life again? Grasshopper has killed me.”

“Yes,” replied Manabozho, who, as quickly as he could, gathered the scattered leaves and branches, renewed its beauty with his breath, and set off. Although Grasshopper in the same way compelled Manabozho to lose time in repairing the hemlock, the sycamore, cedar, and many other trees, the giant did not falter, but pushing briskly forward, was fast overtaking him, when Grasshopper happened to see an elk. And asking him, for old acquaintance’ sake, to take him on his back, the elk did so, and for some time he made good headway, but still Manabozho was in sight.

He was fast gaining upon him, when Grasshopper threw himself off the elk’s back; and striking a great sandstone rock near the path, he broke it into pieces, and scattered the grains in a thousand directions; for this was nearly his last hope of escape. Manabozho was so close upon him at this place that he had almost caught him; but the foundation of the rock cried out,

“Haye! Ne-me-sho, Grasshopper has spoiled me. Will you not restore me to life?”

“Yes,” replied Manabozho. He re-established the rock in all its strength.

He then pushed on in pursuit, and had got so near to Grasshopper as to put out his arm to seize him; but Grasshopper dodged him, and, as his last chance, he immediately raised such a dust and commotion by whirlwinds, as made the trees break and the sand and leaves dance in the air. Again and again Manabozho stretched his arm, but he escaped him at every turn, and kept up such a tumult of dust that he dashed into a hollow tree which had been blown down, changed himself into a snake, and crept out at the roots just in time to save his life; for at that moment Manabozho, who had the power of lightning, struck it, and it was strewn about in little pieces.

Again Grasshopper was in human shape, and Manabozho was pressing him hard. At a distance he saw a very high bluff of rocks jutting out into a lake, and he ran for the foot of the precipice which was abrupt and elevated. As he came near, to his surprise and great relief, the Manito of the rock opened his door and told Grasshopper to come in. The door was no sooner closed than Manabozho knocked.

“Open it!” he cried, with a loud voice. The Manito was afraid of him; but he said to Grasshopper, “Since I have taken you as my guest, I would sooner die with you than open the door.”

“Open it!” Manabozho again cried, in a louder voice than before.

The Manito kept silent. Manabozho, however, made no attempt to open it by force. He waited a few moments.

“Very well,” he said; “I give you till morning to live.”

Grasshopper trembled, for he thought his last hour had come; but the Manito bade him to be of good cheer.

When the night came on the clouds were thick and black, and as they were torn open by the lightning, such discharges of thunder were never heard as bellowed forth. The clouds advanced slowly and wrapped the earth about with their vast shadows as in a huge cloak. All night long the clouds gathered, and the lightning flashed, and the thunder roared, and above all could be heard Manabozho muttering vengeance upon poor little Grasshopper.

“You have led a very foolish kind of life, Grasshopper,” said his friend the Manito.

“I know it—I know it!” Grasshopper answered.

“You had great gifts of strength awarded to you,” said the Manito.

“I am aware of it,” replied Grasshopper.

“Instead of employing it for useful purposes, and for the good of your fellow-creatures, you have done nothing since you became a man but raise whirlwinds on the highways, leap over trees, break whatever you met in pieces, and perform a thousand idle pranks.”

Grasshopper, with great penitence, confessed that his friend the Manito spoke but too truly; and at last his entertainer, with a still more serious manner, said:

“Grasshopper, you still have your gift of strength. Dedicate it to the good of mankind. Lay all of these wanton and vain-glorious notions out of your head. In a word, be as good as you are strong.”

“I will,” answered Grasshopper. “My heart is changed; I see the error of my ways.”

Black and stormy as it had been all night, when morning came the sun was shining, the air was soft and sweet as the summer down and the blown rose; and afar off upon the side of a mountain sat Manabozho, his head upon his knees, languid and cast down in spirit. His power was gone, for now Grasshopper was in the right, and he could touch him no more.

With many thanks, Grasshopper left the good Manito, taking the nearest way home to his own people.

As he passed on, he fell in with an old man who was wandering about the country in search of some place which he could not find. As soon as he learned his difficulty, Grasshopper, placing the old man upon his back, hurried away, and in a short hour’s dispatch of foot set him down among his own kindred, of whom he had been in quest.

Loosing no time, Grasshopper next came to an open plain, where a small number of men stood at bay, and on the very point of being borne down by great odds, in a force of armed warriors, fierce of aspect and of prodigious strength. When Grasshopper saw this unequal struggle, rushing forward he seized a long bare pole, and, wielding it with his whole force, he drove the fierce warriors back; and, laying about him on every hand, he soon sent them a thousand ways in great haste, and in a very sore plight.

Without tarrying to receive the thanks of those to whom he had brought this timely relief, he made his utmost speed, and by the close of the afternoon he had come in sight of his own village. What were his surprise and horror, as he approached nearer, to discover the bears in excellent case and flesh, seated at lazy leisure in the trees, looking idly on while his brother Indians, for their pastime, were dancing a fantastic and wearisome dance, in the course of which they were frequently compelled to go upon all fours and bow their heads in profound obeisance to their bear-masters in the trees.

As he drew nearer, his heart sunk within him to see how starved, and hollow-eyed, and woe-begone they were; and his horror was at its height when, as he entered his own lodge, he beheld his favorite and friend, the Pipe-bearer, also on all fours, smoothing the floor with the palms of his hands to make it a comfortable sitting-place for the bears on their return from the dance.

It did not take Grasshopper a long time to resolve what he should do. He immediately resumed power in the village, bestowed a sound cudgeling upon the bears, and sent them off to live in the mountains, among their own people, as bears should; restored to the people all their rights; gave them plenty to eat and drink; exerting his great strength in hunting, in rebuilding their lodges, keeping in check their enemies, and doing all the good he could to every body.

Peace and plenty soon shone and showered upon the spot; and, never once thinking of all his wild and wanton frolics, the people blessed Grasshopper for all his kindness, and sincerely prayed that his name might be held in honor for a thousand years to come, as no doubt it will.

Little Pipe-bearer stood by Grasshopper in all his course, and admired his ways as much now that he had taken to being orderly and useful, as in the old times, when he was walking a mile a minute, and in mere wantonness bringing home whole forests in his arms for fire-wood, in midsummer.

It was a great old age to which Grasshopper lived, and when at last he came to die, there was not a dry eye in all that part of the world where he spent his latter days.

If you liked this story, leave me a comment down below. Join our Facebook community. And don’t forget to Subscribe!

Enjoy more Native American stories!