THE WOOING OF BECFOLA (IRISH FAIRY TALES) by James Stephens

CHAPTER I

We do not know where Becfola came from. Nor do we know for certain where she went to. We do not even know her real name, for the name Becfola, “Dowerless” or “Small-dowered,” was given to her as a nickname. This only is certain, that she disappeared from the world we know of, and that she went to a realm where even conjecture may not follow her.

It happened in the days when Dermod, son of the famous Ae of Slane, was monarch of all Ireland. He was unmarried, but he had many foster-sons, princes from the Four Provinces, who were sent by their fathers as tokens of loyalty and affection to the Ard-Ri, and his duties as a foster-father were righteously acquitted. Among the young princes of his household there was one, Crimthann, son of Ae, King of Leinster, whom the High King preferred to the others over whom he held fatherly sway. Nor was this wonderful, for the lad loved him also, and was as eager and intelligent and modest as becomes a prince.

The High King and Crimthann would often set out from Tara to hunt and hawk, sometimes unaccompanied even by a servant; and on these excursions the king imparted to his foster-son his own wide knowledge of forest craft, and advised him generally as to the bearing and duties of a prince, the conduct of a court, and the care of a people.

Dermod mac Ae delighted in these solitary adventures, and when he could steal a day from policy and affairs he would send word privily to Crimthann. The boy, having donned his hunting gear, would join the king at a place arranged between them, and then they ranged abroad as chance might direct.

On one of these adventures, as they searched a flooded river to find the ford, they saw a solitary woman in a chariot driving from the west.

“I wonder what that means?” the king exclaimed thoughtfully.

“Why should you wonder at a woman in a chariot?” his companion inquired, for Crimthann loved and would have knowledge.

“Good, my Treasure,” Dermod answered, “our minds are astonished when we see a woman able to drive a cow to pasture, for it has always seemed to us that they do not drive well.”

Crimthann absorbed instruction like a sponge and digested it as rapidly.

“I think that is justly said,” he agreed.

“But,” Dermod continued, “when we see a woman driving a chariot of two horses, then we are amazed indeed.”

When the machinery of anything is explained to us we grow interested, and Crimthann became, by instruction, as astonished as the king was.

“In good truth,” said he, “the woman is driving two horses.”

“Had you not observed it before?” his master asked with kindly malice.

“I had observed but not noticed,” the young man admitted.

“Further,” said the king, “surmise is aroused in us when we discover a woman far from a house; for you will have both observed and noticed that women are home-dwellers, and that a house without a woman or a woman without a house are imperfect objects, and although they be but half observed, they are noticed on the double.”

“There is no doubting it,” the prince answered from a knitted and thought-tormented brow.

“We shall ask this woman for information about herself,” said the king decidedly.

“Let us do so,” his ward agreed

“The king’s majesty uses the words ‘we’ and ‘us’ when referring to the king’s majesty,” said Dermod, “but princes who do not yet rule territories must use another form of speech when referring to themselves.”

“I am very thoughtless,” said Crimthann humbly.

The king kissed him on both cheeks.

“Indeed, my dear heart and my son, we are not scolding you, but you must try not to look so terribly thoughtful when you think. It is part of the art of a ruler.”

“I shall never master that hard art,” lamented his fosterling.

“We must all master it,” Dermod replied. “We may think with our minds and with our tongues, but we should never think with our noses and with our eyebrows.”

The woman in the chariot had drawn nigh to the ford by which they were standing, and, without pause, she swung her steeds into the shallows and came across the river in a tumult of foam and spray.

“Does she not drive well?” cried Crimthann admiringly.

“When you are older,” the king counselled him, “you will admire that which is truly admirable, for although the driving is good the lady is better.”

He continued with enthusiasm.

“She is in truth a wonder of the world and an endless delight to the eye.”

She was all that and more, and, as she took the horses through the river and lifted them up the bank, her flying hair and parted lips and all the young strength and grace of her body went into the king’s eye and could not easily come out again.

Nevertheless, it was upon his ward that the lady’s gaze rested, and if the king could scarcely look away from her, she could, but only with an equal effort, look away from Crimthann.

“Halt there!” cried the king.

“Who should I halt for?” the lady demanded, halting all the same, as is the manner of women, who rebel against command and yet receive it.

“Halt for Dermod!”

“There are Dermods and Dermods in this world,” she quoted.

“There is yet but one Ard-Ri’,” the monarch answered.

She then descended from the chariot and made her reverence.

“I wish to know your name?” said he.

But at this demand the lady frowned and answered decidedly:

“I do not wish to tell it.”

“I wish to know also where you come from and to what place you are going?”

“I do not wish to tell any of these things.”

“Not to the king!”

“I do not wish to tell them to any one.”

Crimthann was scandalised.

“Lady,” he pleaded, “you will surely not withhold information from the Ard-Ri’?”

But the lady stared as royally on the High King as the High King did on her, and, whatever it was he saw in those lovely eyes, the king did not insist.

He drew Crimthann apart, for he withheld no instruction from that lad.

“My heart,” he said, “we must always try to act wisely, and we should only insist on receiving answers to questions in which we are personally concerned.”

Crimthann imbibed all the justice of that remark.

“Thus I do not really require to know this lady’s name, nor do I care from what direction she comes.”

“You do not?” Crimthann asked.

“No, but what I do wish to know is, Will she marry me?”

“By my hand that is a notable question,” his companion stammered.

“It is a question that must be answered,” the king cried triumphantly. “But,” he continued, “to learn what woman she is, or where she comes from, might bring us torment as well as information. Who knows in what adventures the past has engaged her!”

And he stared for a profound moment on disturbing, sinister horizons, and Crimthann meditated there with him.

“The past is hers,” he concluded, “but the future is ours, and we shall only demand that which is pertinent to the future.”

He returned to the lady.

“We wish you to be our wife,” he said. And he gazed on her benevolently and firmly and carefully when he said that, so that her regard could not stray otherwhere. Yet, even as he looked, a tear did well into those lovely eyes, and behind her brow a thought moved of the beautiful boy who was looking at her from the king’s side.

But when the High King of Ireland asks us to marry him we do not refuse, for it is not a thing that we shall be asked to do every day in the week, and there is no woman in the world but would love to rule it in Tara.

No second tear crept on the lady’s lashes, and, with her hand in the king’s hand, they paced together towards the palace, while behind them, in melancholy mood, Crimthann mac Ae led the horses and the chariot.

CHAPTER II

They were married in a haste which equalled the king’s desire; and as he did not again ask her name, and as she did not volunteer to give it, and as she brought no dowry to her husband and received none from him, she was called Becfola, the Dowerless.

Time passed, and the king’s happiness was as great as his expectation of it had promised. But on the part of Becfola no similar tidings can be given.

There are those whose happiness lies in ambition and station, and to such a one the fact of being queen to the High King of Ireland is a satisfaction at which desire is sated. But the mind of Becfola was not of this temperate quality, and, lacking Crimthann, it seemed to her that she possessed nothing.

For to her mind he was the sunlight in the sun, the brightness in the moonbeam; he was the savour in fruit and the taste in honey; and when she looked from Crimthann to the king she could not but consider that the right man was in the wrong place. She thought that crowned only with his curls Crlmthann mac Ae was more nobly diademed than are the masters of the world, and she told him so.

His terror on hearing this unexpected news was so great that he meditated immediate flight from Tara; but when a thing has been uttered once it is easier said the second time and on the third repetition it is patiently listened to.

After no great delay Crimthann mac Ae agreed and arranged that he and Becfola should fly from Tara, and it was part of their understanding that they should live happily ever after.

One morning, when not even a bird was astir, the king felt that his dear companion was rising. He looked with one eye at the light that stole greyly through the window, and recognised that it could not in justice be called light.

“There is not even a bird up,” he murmured.

And then to Becfola.

“What is the early rising for, dear heart?”

“An engagement I have,” she replied.

“This is not a time for engagements,” said the calm monarch.

“Let it be so,” she replied, and she dressed rapidly.

“And what is the engagement?” he pursued.

“Raiment that I left at a certain place and must have. Eight silken smocks embroidered with gold, eight precious brooches of beaten gold, three diadems of pure gold.”

“At this hour,” said the patient king, “the bed is better than the road.”

“Let it be so,” said she.

“And moreover,” he continued, “a Sunday journey brings bad luck.”

“Let the luck come that will come,” she answered.

“To keep a cat from cream or a woman from her gear is not work for a king,” said the monarch severely.

The Ard-Ri’ could look on all things with composure, and regard all beings with a tranquil eye; but it should be known that there was one deed entirely hateful to him, and he would punish its commission with the very last rigour—this was, a transgression of the Sunday. During six days of the week all that could happen might happen, so far as Dermod was concerned, but on the seventh day nothing should happen at all if the High King could restrain it. Had it been possible he would have tethered the birds to their own green branches on that day, and forbidden the clouds to pack the upper world with stir and colour. These the king permitted, with a tight lip, perhaps, but all else that came under his hand felt his control.

It was his custom when he arose on the morn of Sunday to climb to the most elevated point of Tara, and gaze thence on every side, so that he might see if any fairies or people of the Shi’ were disporting themselves in his lordship; for he absolutely prohibited the usage of the earth to these beings on the Sunday, and woe’s worth was it for the sweet being he discovered breaking his law.

We do not know what ill he could do to the fairies, but during Dermod’s reign the world said its prayers on Sunday and the Shi’ folk stayed in their hills.

It may be imagined, therefore, with what wrath he saw his wife’s preparations for her journey, but, although a king can do everything, what can a husband do…? He rearranged himself for slumber.

“I am no party to this untimely journey,” he said angrily.

“Let it be so,” said Becfola.

She left the palace with one maid, and as she crossed the doorway something happened to her, but by what means it happened would be hard to tell; for in the one pace she passed out of the palace and out of the world, and the second step she trod was in Faery, but she did not know this.

Her intention was to go to Cluain da chaillech to meet Crimthann, but when she left the palace she did not remember Crimthann any more.

To her eye and to the eye of her maid the world was as it always had been, and the landmarks they knew were about them. But the object for which they were travelling was different, although unknown, and the people they passed on the roads were unknown, and were yet people that they knew.

They set out southwards from Tara into the Duffry of Leinster, and after some time they came into wild country and went astray. At last Becfola halted, saying:

“I do not know where we are.”

The maid replied that she also did not know.

“Yet,” said Becfola, “if we continue to walk straight on we shall arrive somewhere.”

They went on, and the maid watered the road with her tears.

Night drew on them; a grey chill, a grey silence, and they were enveloped in that chill and silence; and they began to go in expectation and terror, for they both knew and did not know that which they were bound for.

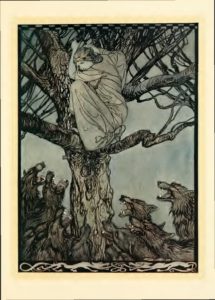

As they toiled desolately up the rustling and whispering side of a low hill the maid chanced to look back, and when she looked back she screamed and pointed, and clung to Becfola’s arm. Becfola followed the pointing finger, and saw below a large black mass that moved jerkily forward.

“Wolves!” cried the maid. “Run to the trees yonder,” her mistress ordered. “We will climb them and sit among the branches.”

They ran then, the maid moaning and lamenting all the while.

“I cannot climb a tree,” she sobbed, “I shall be eaten by the wolves.”

And that was true.

But her mistress climbed a tree, and drew by a hand’s breadth from the rap and snap and slaver of those steel jaws. Then, sitting on a branch, she looked with angry woe at the straining and snarling horde below, seeing many a white fang in those grinning jowls, and the smouldering, red blink of those leaping and prowling eyes.

CHAPTER III

But after some time the moon arose and the wolves went away, for their leader, a sagacious and crafty chief, declared that as long as they remained where they were, the lady would remain where she was; and so, with a hearty curse on trees, the troop departed. Becfola had pains in her legs from the way she had wrapped them about the branch, but there was no part of her that did not ache, for a lady does not sit with any ease upon a tree.

For some time she did not care to come down from the branch. “Those wolves may return,” she said, “for their chief is crafty and sagacious, and it is certain, from the look I caught in his eye as he departed, that he would rather taste of me than cat any woman he has met.”

She looked carefully in every direction to see if one might discover them in hiding; she looked closely and lingeringly at the shadows under distant trees to see if these shadows moved; and she listened on every wind to try if she could distinguish a yap or a yawn or a sneeze. But she saw or heard nothing; and little by little tranquillity crept into her mind, and she began to consider that a danger which is past is a danger that may be neglected.

Yet ere she descended she looked again on the world of jet and silver that dozed about her, and she spied a red glimmer among distant trees.

“There is no danger where there is light,” she said, and she thereupon came from the tree and ran in the direction that she had noted.

In a spot between three great oaks she came upon a man who was roasting a wild boar over a fire. She saluted this youth and sat beside him. But after the first glance and greeting he did not look at her again, nor did he speak.

When the boar was cooked he ate of it and she had her share. Then he arose from the fire and walked away among the trees. Becfola followed, feeling ruefully that something new to her experience had arrived; “for,” she thought, “it is usual that young men should not speak to me now that I am the mate of a king, but it is very unusual that young men should not look at me.”

But if the young man did not look at her she looked well at him, and what she saw pleased her so much that she had no time for further cogitation. For if Crimthann had been beautiful, this youth was ten times more beautiful. The curls on Crimthann’s head had been indeed as a benediction to the queen’s eye, so that she had eaten the better and slept the sounder for seeing him. But the sight of this youth left her without the desire to eat, and, as for sleep, she dreaded it, for if she closed an eye she would be robbed of the one delight in time, which was to look at this young man, and not to cease looking at him while her eye could peer or her head could remain upright.

They came to an inlet of the sea all sweet and calm under the round, silver-flooding moon, and the young man, with Becfola treading on his heel, stepped into a boat and rowed to a high-jutting, pleasant island. There they went inland towards a vast palace, in which there was no person but themselves alone, and there the young man went to sleep, while Becfola sat staring at him until the unavoidable peace pressed down her eyelids and she too slumbered.

She was awakened in the morning by a great shout.

“Come out, Flann, come out, my heart!”

The young man leaped from his couch, girded on his harness, and strode out. Three young men met him, each in battle harness, and these four advanced to meet four other men who awaited them at a little distance on the lawn. Then these two sets of four fought togethor with every warlike courtesy but with every warlike severity, and at the end of that combat there was but one man standing, and the other seven lay tossed in death.

Becfola spoke to the youth.

“Your combat has indeed been gallant,” she said.

“Alas,” he replied, “if it has been a gallant deed it has not been a good one, for my three brothers are dead and my four nephews are dead.”

“Ah me!” cried Becfola, “why did you fight that fight?”

“For the lordship of this island, the Isle of Fedach, son of Dali.”

But, although Becfola was moved and horrified by this battle, it was in another direction that her interest lay; therefore she soon asked the question which lay next her heart:

“Why would you not speak to me or look at me?”

“Until I have won the kingship of this land from all claimants, I am no match for the mate of the High King of Ireland,” he replied.

And that reply was llke balm to the heart of Becfola.

“What shall I do?” she inquired radiantly. “Return to your home,” he counselled. “I will escort you there with your maid, for she is not really dead, and when I have won my lordship I will go seek you in Tara.”

“You will surely come,” she insisted.

“By my hand,” quoth he, “I will come.”

These three returned then, and at the end of a day and night they saw far off the mighty roofs of Tara massed in the morning haze. The young man left them, and with many a backward look and with dragging, reluctant feet, Becfola crossed the threshold of the palace, wondering what she should say to Dermod and how she could account for an absence of three days’ duration.

CHAPTER IV

IT was so early that not even a bird was yet awake, and the dull grey light that came from the atmosphere enlarged and made indistinct all that one looked at, and swathed all things in a cold and livid gloom.

As she trod cautiously through dim corridors Becfola was glad that, saving the guards, no creature was astir, and that for some time yet she need account to no person for her movements. She was glad also of a respite which would enable her to settle into her home and draw about her the composure which women feel when they are surrounded by the walls of their houses, and can see about them the possessions which, by the fact of ownership, have become almost a part of their personality. Sundered from her belongings, no woman is tranquil, her heart is not truly at ease, however her mind may function, so that under the broad sky or in the house of another she is not the competent, precise individual which she becomes when she sees again her household in order and her domestic requirements at her hand.

Becfola pushed the door of the king’s sleeping chamber and entered noiselessly. Then she sat quietly in a seat gazing on the recumbent monarch, and prepared to consider how she should advance to him when he awakened, and with what information she might stay his inquiries or reproaches.

“I will reproach him,” she thought. “I will call him a bad husband and astonish him, and he will forget everything but his own alarm and indignation.”

But at that moment the king lifted his head from the pillow and looked kindly at her. Her heart gave a great throb, and she prepared to speak at once and in great volume before he could formulate any question. But the king spoke first, and what he said so astonished her that the explanation and reproach with which her tongue was thrilling fled from it at a stroke, and she could only sit staring and bewildered and tongue-tied.

“Well, my dear heart,” said the king, “have you decided not to keep that engagement?”

“I—I—!” Becfola stammered.

“It is truly not an hour for engagements,” Dermod insisted, “for not a bird of the birds has left his tree; and,” he continued maliciously, “the light is such that you could not see an engagement even if you met one.”

“I,” Becfola gasped. “I—-!”

“A Sunday journey,” he went on, “is a notorious bad journey. No good can come from it. You can get your smocks and diadems to-morrow. But at this hour a wise person leaves engagements to the bats and the staring owls and the round-eyed creatures that prowl and sniff in the dark. Come back to the warm bed, sweet woman, and set on your journey in the morning.”

Such a load of apprehension was lifted from Becfola’s heart that she instantly did as she had been commanded, and such a bewilderment had yet possession of her faculties that she could not think or utter a word on any subject.

Yet the thought did come into her head as she stretched in the warm gloom that Crimthann the son of Ae must be now attending her at Cluain da chaillech, and she thought of that young man as of something wonderful and very ridiculous, and the fact that he was waiting for her troubled her no more than if a sheep had been waiting for her or a roadside bush.

She fell asleep.

CHAPTER V

In the morning as they sat at breakfast four clerics were announced, and when they entered the king looked on them with stern disapproval.

“What is the meaning of this journey on Sunday?” he demanded.

A lank-jawed, thin-browed brother, with uneasy, intertwining fingers, and a deep-set, venomous eye, was the spokesman of those four.

“Indeed,” he said, and the fingers of his right hand strangled and did to death the fingers of his left hand, “indeed, we have transgressed by order.”

“Explain that.”

“We have been sent to you hurriedly by our master, Molasius of Devenish.”

“A pious, a saintly man,” the king interrupted, “and one who does not countenance transgressions of the Sunday.”

“We were ordered to tell you as follows,” said the grim cleric, and he buried the fingers of his right hand in his left fist, so that one could not hope to see them resurrected again. “It was the duty of one of the Brothers of Devenish,” he continued, “to turn out the cattle this morning before the dawn of day, and that Brother, while in his duty, saw eight comely young men who fought together.”

“On the morning of Sunday,” Dermod exploded.

The cleric nodded with savage emphasis.

“On the morning of this self-same and instant sacred day.”

“Tell on,” said the king wrathfully.

But terror gripped with sudden fingers at Becfola’s heart.

“Do not tell horrid stories on the Sunday,” she pleaded. “No good can come to any one from such a tale.”

“Nay, this must be told, sweet lady,” said the king. But the cleric stared at her glumly, forbiddingly, and resumed his story at a gesture.

“Of these eight men, seven were killed.”

“They are in hell,” the king said gloomily.

“In hell they are,” the cleric replied with enthusiasm.

“And the one that was not killed?”

“He is alive,” that cleric responded.

“He would be,” the monarch assented. “Tell your tale.”

“Molasius had those seven miscreants buried, and he took from their unhallowed necks and from their lewd arms and from their unblessed weapons the load of two men in gold and silver treasure.”

“Two men’s load!” said Dermod thoughtfully.

“That much,” said the lean cleric. “No more, no less. And he has sent us to find out what part of that hellish treasure belongs to the Brothers of Devenish and how much is the property of the king.”

Becfola again broke in, speaking graciously, regally, hastily: “Let those Brothers have the entire of the treasure, for it is Sunday treasure, and as such it will bring no luck to any one.”

The cleric again looked at her coldly, with a harsh-lidded, small-set, grey-eyed glare, and waited for the king’s reply.

Dermod pondered, shaking his head as to an argument on his left side, and then nodding it again as to an argument on his right.

“It shall be done as this sweet queen advises. Let a reliquary be formed with cunning workmanship of that gold and silver, dated with my date and signed with my name, to be in memory of my grandmother who gave birth to a lamb, to a salmon, and then to my father, the Ard-Ri’. And, as to the treasure that remains over, a pastoral staff may be beaten from it in honour of Molasius, the pious man.”

“The story is not ended,” said that glum, spike-chinned cleric.

The king moved with jovial impatience.

“If you continue it,” he said, “it will surely come to an end some time. A stone on a stone makes a house, dear heart, and a word on a word tells a tale.”

The cleric wrapped himself into himself, and became lean and menacing. He whispered: “Besides the young man, named Flann, who was not slain, there was another person present at the scene and the combat and the transgression of Sunday.”

“Who was that person?” said the alarmed monarch.

The cleric spiked forward his chin, and then butted forward his brow.

“It was the wife of the king,” he shouted. “It was the woman called Becfola. It was that woman,” he roared, and he extended a lean, inflexible, unending first finger at the queen.

“Dog!” the king stammered, starting up.

“If that be in truth a woman,” the cleric screamed.

“What do you mean?” the king demanded in wrath and terror.

“Either she is a woman of this world to be punished, or she is a woman of the Shi’ to be banished, but this holy morning she was in the Shi’, and her arms were about the neck of Flann.”

The king sank back in his chair stupefied, gazing from one to the other, and then turned an unseeing, fear-dimmed eye towards Becfola.

“Is this true, my pulse?” he murmured.

“It is true,” Becfola replied, and she became suddenly to the king’s eye a whiteness and a stare. He pointed to the door.

“Go to your engagement,” he stammered. “Go to that Flann.”

“He is waiting for me,” said Becfola with proud shame, “and the thought that he should wait wrings my heart.”

She went out from the palace then. She went away from Tara: and in all Ireland and in the world of living men she was not seen again, and she was never heard of again.

If you liked this story, leave me a comment down below. Join our Facebook community. And don’t forget to Subscribe!

You might also enjoy other stories by James Stephens.